Brigid's Anvil: Fire, Healing, and the Forge of the Body

Brigid’s Anvil weaves embodied fire wisdom, Celtic seasonal tradition, and historical insight to trace how a powerful flame healer of forge, birth, and transformation was softened into a demure Catholic saint, without extinguishing the deeper truth her fire still carries.

THE TURNINGSMOKE & SALT

Jen Coombe

1/20/20268 min read

Brigid’s Anvil is a meditation on fire as healer, forge, and threshold. Drawing on Celtic tradition, embodied physiology, and seasonal wisdom, it explores how heat calms the nervous system, burns away what does not belong, and shapes new life through attentive transformation. Brigid appears not as a saint or symbol, but as the living force of tended flame, reminding us that survival, creation, and renewal are forged in warmth, patience, and presence.

Brigid's Anvil: Fire, Healing, and the Forge of the Body

Sit in front of a fire and watch what happens to your breath. Not the metaphorical fire of inspiration or passion, but an actual flame: candle, hearth, campfire, anything that flickers and holds your gaze. Within minutes, sometimes seconds, your nervous system downshifts. Your shoulders drop. Your jaw unclenches. The parasympathetic state, the body's rest-and-repair mode, arrives faster through fire gazing than through almost any other practice. We think of meditation as a skill we have to learn, but fire does the work for us. It's an even older technique. Humans have been softening in the presence of flames since before we had language for what we were doing.

Fire heals by its very nature. The body knows this. When infection takes hold, the body raises its own heat: fever as forge, burning out what doesn't belong. It's not comfortable, but it's precise. The immune system doesn't negotiate; it transforms through intensity, through raising the temperature until the pathogen can't survive. Ancient medicine understood this. Sweat lodges, hot baths, the application of heat to wounds, all of it working with the body's inherent knowledge that sometimes healing requires burning away what's poisoning the system.

This is Brigid's domain. Not the saint the Church tried to make her, demure and chaste, but the older force beneath that name: goddess of fire, forge, healing, poetry, and the liminal heat of birth. In Celtic and Irish tradition, Brigid (also spelled Bríg, Brigit, or Brid) governed the transformative work of flame in all its forms. She presided over the blacksmith's anvil, where metal was heated, struck, and shaped into tools. She watched over the laboring body, where heat and pressure bring forth new life. She inspired the poet, whose breath gave form to what had been previously unspoken. Heat, milk, poetry: these aren't separate attributes but facets of the same creative force, the same commitment to transformation through tended fire.

Historical sources for the goddess Brigid are fragmentary, as with most pre-Christian Irish deities. What we know comes largely from medieval Irish texts compiled by Christian monks, particularly the Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of Invasions) and the Cath Maige Tuired (The Second Battle of Mag Tuired), which describe her as the daughter of the Dagda, one of the chief gods of the Tuatha Dé Danann (sacred-texts.com). In Cormac's Glossary, a 9th-century text, Brigid is described as a goddess whom poets worshipped, and she is associated with healing, childbirth, fire, and smithcraft (sacred-texts.com).

At Imbolc, celebrated at the beginning of February (traditionally February 1st), Brigid's feast marks a threshold moment in the wheel of the year. The name itself comes from Old Irish i mbolg, meaning "in the belly": the earth is pregnant with spring, but hasn't yet delivered. The ewes begin to lactate, their bodies preparing for lambs that haven't yet arrived. Milk flows in anticipation, nourishment preceding birth. This is the season of hidden gestation, of warmth quietly gathering strength beneath the cold. Candles and hearth fires were lit in Brigid's honor, not as a celebration but as participation in the slow return of light. The flame in winter is both prayer and pragmatism, a reminder that warmth is survival, that tending the fire is sacred work because survival itself is sacred.

The connection between Imbolc and the lactation of sheep is deeply rooted in the agrarian calendar of pre-Christian Ireland and Scotland. February marks the beginning of lambing season in these northern climates, when ewes' milk would begin flowing again after the lean winter months. This return of milk represented both literal sustenance and symbolic renewal, the first tangible sign that the land was turning back toward abundance (britannica.com).

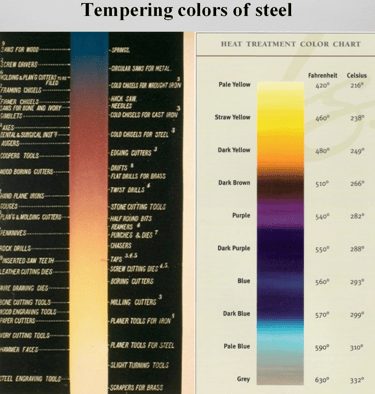

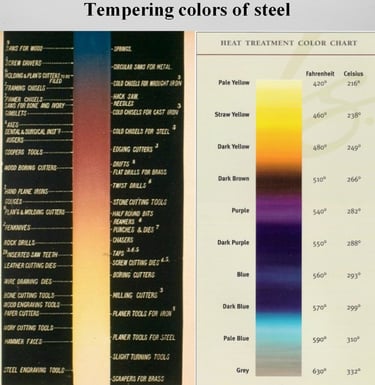

The anvil is Brigid's altar, and the blade is what she births there. Metalworking, before the precision of modern thermometers and controlled atmospheres, required a different kind of knowing. The blacksmith watched the steel in the fire, waiting for the exact color that meant the metal was ready: not too cool, not too hot, but perfectly malleable, receptive to the hammer's strike. This wasn't guesswork. It was attention so refined it became intuition, the eye trained to see what instruments couldn't yet measure.

Blacksmiths learned to read a spectrum of color in heated metal, from dull red (around 1000°F) through bright orange to yellow-white (approaching 2400°F). Each color indicated a different state of workability, and different tasks required different heats. This visual temperature reading remained the primary method of metalworking until the invention of reliable pyrometers in the late 19th century. The knowledge was passed from master to apprentice through years of training, watching the fire, and learning to see (britannica.com).

The smith gazed into the flame the way a midwife reads the laboring body, looking for the signs that say now. The blade emerged from that marriage of heat, timing, and skill: a tool, yes, but also a poem, a thing made by watching and waiting and knowing when to act.

And the blade itself, we should say clearly, is not only a weapon. It's a plow. A scythe. A knife for cutting bread, for carving wood, for the hundred daily tasks that sustain life. Brigid's fire forges tools for survival and creation as much as for war, and the difference lies not in the object but in the hand that wields it and the need it serves. To reduce the anvil's work to violence is to miss the complexity of what metalworking meant in an agricultural world: the hinge, the cauldron, the needle. All of it born from heat and human attention.

This is why Brigid holds poetry alongside smithcraft. Not because she's patroness of unrelated skills, but because metalworking is a kind of poetry: the shaping of raw material into form through disciplined attention, through knowledge passed hand to hand, through the patience to wait for the precise moment when transformation becomes possible. The poet works with breath and sound the way the smith works with fire and iron. Both are makers. Both require the ability to see what isn't yet visible, to sense when the formless is ready to take shape.

The early Church recognized Brigid's power and did what it has always done with feminine forces it cannot destroy: it either demonizes or baptizes... The goddess became a Saint, her mythology folded into Christian narrative, her fire made safe and small. Saint Brigid of Kildare (also known as Brigid of Ireland) is one of Ireland's three primary patron saints, alongside Patrick and Columba. Her feast day remains February 1st, directly overlaying the pagan Imbolc. The Bethu Brigte (Life of Brigit), compiled in the 9th century, and other hagiographies present her as abbess of Kildare, born around 451 CE, though historians generally agree that much of her story absorbed attributes and cult practices of the earlier goddess (britannica.com).

At Kildare, a perpetual flame was tended by nuns in Brigid's honor, a practice that persisted until the 16th-century suppression of the monasteries under Henry VIII. This sacred fire was said to be surrounded by a hedge that no man could cross, and nineteen nuns took turns keeping it alight, with Brigid herself said to tend it on the twentieth night. The parallel to pre-Christian fire-tending rituals is unmistakable (sacred-texts.com).

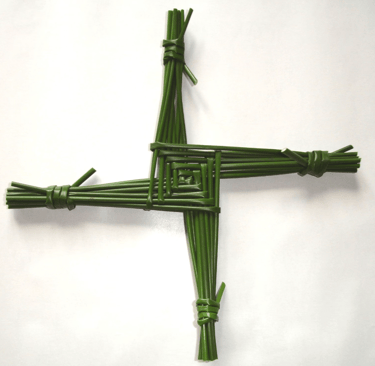

Saint Brigid is still a keeper of hearths and a friend to women in childbirth, but she's also chaste, obedient, and contained. Her miracles are gentle. Her flames don't threaten. The Brigid's cross, woven from straw or rushes, became a Christian symbol, but its form betrays older knowledge. It's square, not cruciform in the suffering sense, echoing the four-armed wheel of the year, the turning of seasons, the cyclical time the Church tried to replace with linear salvation. The cross of straw is about renewal, not atonement. It's a threshold charm, a blessing on the house, a warding against harm. It remembers what the saint was made to forget.

The Brigid's cross traditionally features four arms radiating from a woven center square, typically made from rushes gathered on the eve of her feast day. These crosses were hung above doors, in barns, and over hearths as protection against fire, lightning, and illness. While later Christian tradition frames them as symbols of Brigid's conversion work, their square solar form and seasonal construction suggest much older protective and seasonal magic (sacred-texts.com). This stands in stark contrast to the Christian cross as it later evolved, no longer a marker of seasonal protection and renewal but a symbol of suffering, obedience, and sanctified torture, shifting spiritual focus away from cyclical life and embodied continuity toward sacrifice and redemption through pain.

To reclaim Brigid is to reclaim fire as something other than what we've been taught to fear or sentimentalize. Fire that heals through intensity. Fire that forges the tools we need to survive. Fire that labors to bring forth what didn't exist before. Fire that requires us to watch, to tend, to know when to feed it and when to let it burn down to coals. The flame in February, in the belly of winter, is not decorative. It's the warmth we'll die without, the heat that makes milk flow, the forge where the new year's tools are being shaped in the dark.

Sit with a candle this month, if you can. Not as a ritual performance, but as a practice of presence. Watch what the flame does. Notice when it steadies, when it flickers, when it needs more air or less. Let your gaze soften the way it wants to. Let your breath slow. This is parasympathetic knowledge, older than saints, older than goddesses, old as the first human who sat down beside a fire and felt their body remember it was safe enough to rest. Brigid is there in that softening, not as a figure to petition, but as the heat itself, the force that burns clean, that shapes what's useful, that labors to bring the world forward into light.

With Love & Liberty

Jen Coombe ✨ alias ~ Jennadea